After studying about Data Structured and Algorithms, I put together some annotations that I believe are useful if you need to revisit some topics or to understand a topic for the first time.

Courses I can recommend:

- Comparing Code

- Big O

- Linked Lists

- Doubly Linked List

- Stacks

- Queues

- Trees

- Binary Search Tree

- Hash Tables

- Graphs

- Heap

- Recursion

- Recursive Binary Search Tree

- Algorithms

- Tree Traversal

- Thank you

Table of contents generated with markdown-toc

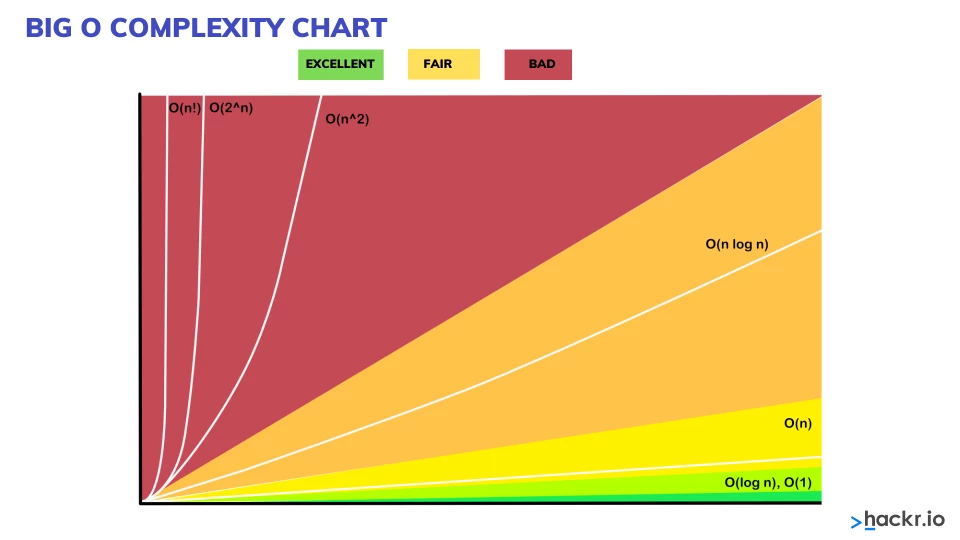

When two codes accomplish the same thing, how can you compare those? Big O is a way to compare code1 and code2 mathematically about how efficiently they run.

Imagine code1 was fully executed in 30 seconds, and code2 took 1 minute to fully execute. Based on this you can say that code1 is better than code2, this is called Time Complexity.

The funny thing about Time Complexity is that is not measured in time. Because if you take code2 and run in a 2 times faster computer, it would run in 30 seconds as well. So Time Complexity it's measured in the number of operations to complete something.

In addition, a Time Complexity we measure Space Complexity. Let's say code1 runs very fast, but it takes a lot of memory when it runs. Maybe code2, even taking 1 minute, takes far less memory when it runs.

In Complexity, we are going to see a lot the greek letters: OMEGA, TETA, OMICRON (O)

Imagine an array:

[1,2,3,4,5,6,7]

The best case is if we are looking for number 1, so we use letter OMEGA Ω

[1,2,3,4,5,6,7]

The average case is if we are looking for number 4, so we use letter TETA Θ

[1,2,3,4,5,6,7]

The worst case is if we are looking for number 7, so we use letter OMICRON Ο

[1,2,3,4,5,6,7]

Big O is always to define worst case.

To explain this notation we are going to use a simple method:

public static void printItems(int n) {

for(int i=0; i < n; i++) {

System.out.println(i);

}

}

When calling this method we get the output:

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

This code is O(n), because we had a number n, that was 10, and we did 10 operations on our for loop.

X = Collection Size = n

Y = Execution time

For the same method, let's add a second for loop:

public static void printItems(int n) {

for(int i=0; i < n; i++) {

System.out.println(i);

}

for(int j=0; j < n; j++) {

System.out.println(j);

}

}

Output:

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

In this case we had n+n operations, so we might think that this would be O(2n), but we simplify this by dropping the constants, so it becomes O(n).

To make our function O(n^2) what we have to do is place one for loop inside the other:

public static void printItems(int n) {

for(int i=0; i < n; i++) {

for(int j=0; j < n; j++) {

System.out.println(i + " " + j);

}

}

}

Output:

0 0

0 1

0 2

0 3

0 4

...

7 6

7 7

7 8

7 9

8 0

8 1

...

9 7

9 8

9 9

So we passed 10 to the function and we got 100 lines. So the for loops ran n * n times, or n^2. That is O(n^2).

Comparison between O(n) and O(n^2):

O(n^2) grows much faster, that means from a time complexity perspective, it is less efficient.

So if you face any code with the complexity of O(n^2), and you can rewrite the code to make it O(n), that's a huge gain of efficiency.

If we add another loop after the nested for loops.

public static void printItems(int n) {

for(int i=0; i < n; i++) {

for(int j=0; j < n; j++) {

System.out.println(i + " " + j);

}

}

for(int k=0; k < n; k++) {

System.out.println(k);

}

}

We will see 110 outputs. So when calculating:

- Nested for loop: O(n^2)

- for loop: O(n)

Total would be O(n^2 + n).

Now imagine we use bigger values as input, the n^2 part would be dominant, as it would increase a lot. The n part would not be so dominant for the end result as the n^2.

So for calculating the complexity we just drop the non-dominants.

Final value would be then O(n^2).

Doesn't matter the n value, there will always be ONE operation. For example:

public static int addItems(int n) {

return n+n;

}

As n grows, the number of operations would stay the same.

What if we add one more operation?

public static int addItems(int n) {

return n+n+n;

}

That would be O(2), so we can simplify this saying O(1).

The O(1) is also called constant time, as n grows the number of operations stays constant.

For this we need a sorted array:

[1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8]

Let's say we need to find a particular value in this array. We want to find the number 1.

The quickest way would be to cut the array in half and see if the number 1 is in the first half or in the second.

[1,2,3,4 [5,6,7,8]

As it is not in the second half, we don't need to look at any of there numbers.

[1,2,3,4 . [5,6,7,8].

Imagine if we had an array with a million values in it, this logic would cut out half a million items we don't have to look at.

Now we can do the same process again:

[1,2] . [3,4].

And again:

[1] . [2].

So we find the number 1 that we were looking for.

If you count now how many steps it took to find the number 1, we see that 3 operations were necessary to find it.

1 - [1,2,3,4 . [5,6,7,8].

2 - [1,2] . [3,4].

3 - [1] . [2].

So took 3 steps and we had 8 items in the array.

2^3 = 8

if we try to convert this equation to a log, we get to:

log2 8 = 3

This is basically saying:

- 2 to what power is equal 8? That's 3.

or

- If you took the number 8 and repeatedly divided by two, how many times would it take to get down to one item? That's 3 times

The real power of this is when dealing with very large number:

Imagine

log2 1.073.741.824 = 3

How many times would we need to cut this number in half to get down to one item?

You could have an array with a billion items in it and find any number in that array in 31 steps.

Imagine that now we have two parameters instead of one.

public static void printItems(int a, int b) {

for(int i=0; i < a; i++) {

System.out.println(i);

}

for(int j=0; j < b; j++) {

System.out.println(j);

}

}

There is a gotcha on this question. By calculating you would say that's two for loops, so O(n) + O(n).

So we would have O(2n), and by dropping the constant O(n), but that is NOT CORRECT. Because this way you are implying that a = b = n, and you can't do that.

We have to say that the first loop is O(a) and the second O(b), so the result would be O(a + b).

Same applies if we nested the for loops.

public static void printItems(int a, int b) {

for(int i=0; i < a; i++) {

for(int j=0; j < b; j++) {

System.out.println(i + " " + j);

}

}

}

The complexity would be O(a * b).

We can't just say that they are equal to n, we have to use different terms for different inputs.

myList = [11, 3, 23, 7]

| values | 11 | 3 | 23 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| index | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

myList.add(17)

| values | 11 | 3 | 23 | 7 | 17 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| index | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

This add(17) operation didn't require any re-indexing. So it's a O(1) operation.

myList.remove(4) is a

| values | 11 | 3 | 23 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| index | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

This remove(4) operation didn't require any re-indexing. So it's a O(1) operation as well.

Now if we do: myList.remove(0)

| values | 3 | 23 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|

| index | 1 | 2 | 3 |

We notice that the value 3 is no longer at correct index. So we need to re-index.

| values | 3 | 23 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|

| index | 0 |

2 | 3 |

| values | 3 | 23 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|

| index | 0 | 1 |

3 |

| values | 3 | 23 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|

| index | 0 | 1 | 2 |

So we need to touch every element of the list.

Same happens if we do: myList.add(0, 11)

| values | 11 |

3 | 23 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| index | 0 |

0 | 1 | 2 |

| values | 11 | 3 | 23 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| index | 0 | 1 |

1 | 2 |

| values | 11 | 3 | 23 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| index | 0 | 1 | 2 |

2 |

| values | 11 | 3 | 23 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| index | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

Because we had to touch each item, this is O(n).

So it's O(1) on this end to add or remove something.

| values | 11 | 3 | 23 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| index | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

But it is O(n) to add/remove on this end. Because of the re-index.

| values | 11 |

3 | 23 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| index | 0 |

1 | 2 | 3 |

Even if we do: myList.add(1, 99)

| values | 11 | 99 |

3 | 23 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| index | 0 | 1 |

1 | 2 | 3 |

We are going to touch all the items after the index where the add/remove happened.

| values | 11 | 99 | 3 | 23 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| index | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

So that's O(n).

What if we do: myList.find(7)

| values | 11 |

3 | 23 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| index | 0 |

1 | 2 | 3 |

| values | 11 | 3 |

23 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| index | 0 | 1 |

2 | 3 |

| values | 11 | 3 | 23 |

7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| index | 0 | 1 | 2 |

3 |

| values | 11 | 3 | 23 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| index | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

Looking for a value by value is O(n)

But is different if we are looking by index myList.get(3):

| values | 11 | 3 | 23 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| index | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

That would be O(1).

Imagine n = 100:

O(1) = 1

O(log n) ≈ 7

O(n) = 100

O(n^2) = 100

We can clearly see the difference between the values. O(n^2) compared to the others is very inefficient.

Now imagine n = 1000:

O(1) = 1

O(log n) ≈ 10

O(n) = 1000

O(n^2) = 1000000

O(n^2) is going to grow very fast, as we can see.

| O(1) | O(log n) | O(n) | O(n^2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | Divide and Conquer | Proportional | Loop within a loop |

More information regarding time complexity of data structures and array sorting algorithms in the website:

https://www.bigocheatsheet.com/

By comparing with an array list, it's

linked lists are dynamic and linked just like array lists, whereas arrays are fixed in length.

linked lists don't have indexes

| 11 | 3 | 23 | 7 |

|---|

another difference is that with a linked lists, instead of all the items being in a contiguous place in memory, they are going to be spread out.

| 11 | 3 | 23 | 7 |

|---|

Linked List is also going to have a variable called head that points to the first node ad one called tail, that points to the last node.

| 11 | 3 | 23 | 7 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| head | tail |

Each node is going to have a pointer that points to the next node, and the next, and the next, and so on until we get to the end.

| 11 | → | 3 | → | 23 | → | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| head | tail |

The last node just points to NULL, but it does have a variable there for the pointer.

If you look at the linked list in memory, is all over the place like this, with each one pointing to the next.

So if we compare this to an array list, those data structures are going to be in a contiguous place in memory. And that's why on those data structures we can have indexes.

For example, we have a linked list

| 11 | → | 3 | → | 23 | → | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| head | tail |

The steps that we would do is we are going to have the last pointing to it:

| 11 | → | 3 | → | 23 | → | 7 | → | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| head | tail |

The tail pointer would point to it as well:

| 11 | → | 3 | → | 23 | → | 7 | → | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| head | tail |

Having in mind that n is the number of nodes. So the steps are going to be the same if the linked list has 10 items, or it has 1000 items in it.

it's not going to change based on n. Meaning it would be O(1).

For removing the last item it can appear to be the same complexity, but it's not

last item: 4

| 11 | → | 3 | → | 23 | → | 7 | → | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| head | tail |

We need to point the tail to the item 23, but from the item 4 perspective, we don't have a pointer to the previous item.

We can't go backwards in the Linked List.

| 11 | → | 3 | → | 23 | → | 7 | → | ∅ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| head | tail |

We are going to need to start at the head and iterate through the list until we get to the item pointing to NULL, in other words, the last item.

| 11 | → | 3 | → | 23 | → | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| head | tail |

Because we had to touch every node and iterate through the list, this is O(n).

| 11 | → | 3 | → | 23 | → | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| head | tail |

We are going to move the head to the new node

| 4 | 11 | → | 3 | → | 23 | → | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| head | tail |

And connect the new node to the first item (11).

| 4 | → | 11 | → | 3 | → | 23 | → | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| head | tail |

So it doesn't matter how much items we have in the linked list. We will always do a fixed number of operations.

Meaning that is O(1).

We are going to move the head to the head.next node

| 4 | → | 11 | → | 3 | → | 23 | → | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| head | tail |

And then we remove the node 4 from the list by pointing it to null.

| 4 | 11 | → | 3 | → | 23 | → | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| head | tail |

Resulting in:

| 11 | → | 3 | → | 23 | → | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| head | tail |

So it doesn't matter how much items we have in the linked list. We will always do a fixed number of operations.

Meaning that is O(1).

Adding an item at index 3 means it will be after the 23 node

| 11 | → | 3 | → | 23 | → | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| head | tail |

As our items are all over the place in memory, we don't have access through indexes.

So because of that we start from the head and iterate through this list and get to a node where node.next = index 3.

| 11 | → | 3 | → | 23 | → | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| head | .↑ | tail |

When we reach the correct node having the next as index 3 (23 node) we point the new node to it.

| 11 | → | 3 | → | 23 | → | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ↑ | ||||||

| 4 | ||||||

| head | tail |

And the node that we are currently (23 node) points to the new node (node.next = 4).

| 11 | → | 3 | → | 23 | → | 4 | → | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| head | tail |

Because we had to iterate through the list to find the element on index 3, this is O(n).

Remove item at specific index 3

| 11 | → | 3 | → | 23 | → | 4 | → | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| head | tail |

We need to start from the head and iterate through this list and get to a node where node.next = index 3.

We want the 23 to point to the 7 node, as the 4 points to it, we are going to set the pointer for the 23 to be equal to that.

And we point the 4 node to NULL, so it removes the node from the list.

| 11 | → | 3 | → | 23 | → | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| head | tail |

Because we had to iterate through the list to find the element on index 3, this is O(n).

What if we want to look for an item that has value 23?

| 11 | → | 3 | → | 23 | → | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| head | tail |

We need to start from the head and iterate through this list and get to a node where value is 23.

Because we had to iterate through the list to find the element on index 3, this is O(n).

So it doesn't matter if we look for something by value or by index, it is O(n).

That's one of the places where an Array List is better than a Linked List. Because it has the direct access by index.

- Better

| Linked List | Array List | |

|---|---|---|

| Append | O(1) | O(1) |

| Remove Last | O(n) | O(1) |

| Prepend | O(1) |

O(n) |

| Remove First | O(1) |

O(n) |

| Insert | O(n) | O(n) |

| Remove | O(n) | O(n) |

| Lookup by Index | O(n) | O(1) |

| Lookup by Value | O(n) | O(n) |

We can represent each node in a JSON like this:

{

"value"=11,

"next"= null

}

Our entire Linked List could be represented by something like:

head={

"value"=11,

"next"= {

"value"=3,

"next"= {

"value"=23,

"next"= {

"value"=7,

tail= "next"= null

}

}

}

}

| 11 | → | 3 | → | 23 | → | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| head | tail |

Let's implement the constructor for the LinkedList and the Node class:

public class LinkedList {

private Node head;

private Node tail;

private int length;

public LinkedList(int value){

Node newListNode = new Node(value);

head = newListNode;

tail = newListNode;

length = 1;

}

class Node {

private final int value;

private Node next;

public Node(int value) {

this.value = value;

}

}

}

Java code:

public void reverse() {

Node temp = head;

head = tail;

tail = temp;

Node after;

Node before = null;

for (int i = 0; i < length; i++) {

after = temp.next;

temp.next = before;

before = temp;

temp = after;

}

}

Java code:

public Node findKthFromEnd(int k) {

Node fastPointer = head;

Node slowPointer = head;

for(int i = 0; i < k; i++) {

if(fastPointer == null) return null;

fastPointer = fastPointer.next;

}

while(fastPointer != null) {

slowPointer = slowPointer.next;

fastPointer = fastPointer.next;

}

return slowPointer;

}

In the LinkedList class, implement a method called reverseBetween that reverses the nodes of the list between indexes m and n (inclusive).

Java code:

public void reverseBetween(int m, int n) {

if(head == null || m == n) return;

Node dummy = new Node(0);

dummy.next = head;

Node prev = dummy;

for(int i = 0; i < m; i++) {

prev = prev.next;

}

Node current = prev.next;

for(int i = 0; i < n-m; i++) {

Node temp = current.next;

current.next = temp.next;

temp.next = prev.next;

prev.next = temp;

}

head = dummy.next;

dummy.next = null;

}

They are very similar to a singly linked list.

The only difference being that we have arrows that go the other way.

| 11 | ⇆ | 3 | ⇆ | 23 | ⇆ | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| head | tail |

We said we could represent a singly linked list node like thid in JSON:

{

"value"=11,

"next"= null

}

Meaning that our Node class would be:

class Node {

private final int value;

private Node next;

public Node(int value) {

this.value = value;

}

}

The only difference with the double linked list is that it has a pointer to the previous node:

class Node {

private final int value;

private Node next;

private Node prev;

public Node(int value) {

this.value = value;

}

}

The code for a Doubly Linked List would look like this:

public class DoublyLinkedList {

private Node head;

private Node tail;

private int length;

public DoublyLinkedList(int value) {

Node newNode = new Node(value);

head = newNode;

tail = newNode;

length = 1;

}

public void printList() {

if (length == 0) {

System.out.println("{} length: 0");

return;

}

var cursor = head;

var output = new StringBuilder("{");

while (cursor != null) {

output.append(cursor.value + (cursor.next != null ? " -> " : ""));

cursor = cursor.next;

}

output.append("} length: " + length);

System.out.println(output);

}

public Node getHead() {

return head;

}

public Node getTail() {

return tail;

}

public int getLength() {

return length;

}

public class Node {

int value;

Node next;

Node prev;

public Node(int value) {

this.value = value;

}

public int getValue() {

return value;

}

public Node getNext() {

return next;

}

public Node getPrev() {

return prev;

}

public void setNext(Node next) {

this.next = next;

}

@Override

public String toString() {

return "{" + value + "}";

}

}

}

public void append(int value) {

Node newNode = new Node(value);

if(length == 0) {

head = newNode;

} else {

tail.next = newNode;

newNode.prev = tail;

}

tail = newNode;

}

public Node removeLast() {

if(length == 0) return null;

Node removedNode = tail;

if(length == 1) {

head = null;

tail = null;

} else {

tail = tail.prev;

tail.next = null;

removedNode.prev = null;

}

length--;

return removedNode;

}

public void prepend(int value) {

Node newNode = new Node(value);

if (length == 0) {

tail = newNode;

} else {

newNode.next = head;

head.prev = newNode;

}

head = newNode;

length++;

}

public Node removeFirst() {

if (length == 0) return null;

Node temp = head;

if(length == 1) {

head = null;

tail = null;

} else {

head = head.next;

head.prev = null;

temp.next = null;

}

length--;

return temp;

}

Similar to the linked list get() method.

The difference is that we first check if the index is closer to the end or the beginning, and based on that we iterate starting from the head forward or from the tail backwards.

public Node get(int index) {

if(index < 0 || index >= length) return null;

Node temp = head;

// If statement to check if we need to start the loop from **start-to-finish** or from the **end-to-beginning**

if(index < length/2) {

for(int i = 0; i < index; i++){

temp = temp.next;

}

} else {

temp = tail;

for(int i = length - 1; i > index; i--){

temp = temp.prev;

}

}

return temp;

}

This is the only method that is the exact same as the singly linked list.

But there is a difference in how the code runs.

Doubly linked list get() method runs differently (and more effectively) then get() method of the singly linked list.

But the code of this method, is exactly the same.

public boolean set(int index, int value) {

Node temp = get(index);

if (temp != null) {

temp.value = value;

return true;

}

return false;

}

public boolean insert(int index, int value) {

if (index < 0 || index > length) return false;

if (index == 0) {

prepend(value);

return true;

}

if (index == length) {

append(value);

return true;

}

Node newNode = new Node(value);

Node before = get(index - 1);

Node after = before.next;

newNode.prev = before;

newNode.next = after;

before.next = newNode;

after.prev = newNode;

length++;

return true;

}

public Node remove(int index) {

if (index < 0 || index >= length) return null;

if (index == 0) return removeFirst();

if (index == length - 1) return removeLast();

Node temp = get(index);

temp.next.prev = temp.prev;

temp.prev.next = temp.next;

temp.next = null;

temp.prev = null;

length--;

return temp;

}

Given a doubly linked list, write a method called swapFirstLast() that swaps the values of the first and last nodes in the list.

public void swapFirstLast() {

if(length < 2) return;

int temp = head.value;

head.value = tail.value;

tail.value = temp;

}

public void reverse() {

Node prev = null;

while(head != null) {

Node next = head.next;

head.next = prev;

head.prev = next;

prev = head;

head = next;

}

}

Write a method to determine whether a given doubly linked list reads the same forwards and backwards.

public boolean isPalindrome() {

Node startNode = head;

Node endNode = tail;

for (int i = 0; i < length / 2; i++) {

if (startNode.value != endNode.value) {

return false;

}

startNode = startNode.next;

endNode = endNode.prev;

}

return true;

}

Implement a method called swapPairs within the class that swaps the values of adjacent nodes in the linked list. The

method should not take any input parameters.

1-->2-->3-->4--> should become 2-->1-->4-->3-->

public void swapPairs() {

if(length <= 1) return;

Node dummy = new Node(0);

dummy.next = head;

head.prev = dummy;

Node first;

Node second;

Node prev = dummy;

while(head != null && head.next != null) {

first = head;

second = head.next;

prev.next = second;

first.next = second.next;

second.next = first;

second.prev = prev;

first.prev = second;

if(first.next != null) {

first.next.prev = first;

}

head = first.next;

prev = first;

}

head = dummy.next;

}

We can think of a stack as if it was a can of tennis balls.

| ㅤ |

| ㅤ |

| ㅤ |

If we add one ball, or in other words push an item onto the stack

| ㅤ |

| ㅤ |

| ◍ |

And another one:

| ㅤ |

| ◍ |

| ◍ |

What makes a stack is that you can only get to the last item that you pushed onto the stack.

You can't get the first pushed item unless you remove the second one.

Then when you push a third ball:

| ◍ |

| ◍ |

| ◍ |

We can't get to the second one. The only one we can get to is the one in the TOP.

That's called LIFO. Last In, First Out.

| ◍ | reacheable |

| ◍ | |

| ◍ |

| ㅤ | |

| ◍ | reacheable |

| ◍ |

| ㅤ | |

| ㅤ | |

| ◍ | reacheable |

When we navigate using our browser, let's say from facebook to YouTube, and then to instagram and later check our email.

What we are doing is creating a stack, with all the previous websites that we have visited.

| Gmail |

| YouTubeㅤ |

| Facebookㅤ |

So when we hit the back button we are popping an item off of the stack.

| YouTubeㅤ |

| Facebookㅤ |

| YouTubeㅤ |

| Facebookㅤ |

A common way to implement a stack is with an array list. It works better than an array here because we don't know how many items we're going to be adding to the stack, so it's better to have a dynamic data structure.

| values | 11 | 3 | 23 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| index | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

So if we add or remove an item to the end of the stack:

| values | 11 | 3 | 23 | 7 | 17 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| index | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| values | 11 | 3 | 23 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| index | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

Both would be O(1) as we don't need to do any other operations life shifting elements, for example.

However, if we add this on the other end:

| values | 3 | 23 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| index | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

We have to do all the re-indexing:

| values | 3 | 23 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| index | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| values | 3 |

23 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| index | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| values | 3 | 23 |

7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| index | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| values | 3 | 23 | 7 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| index | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| values | 3 | 23 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|

| index | 0 | 1 | 2 |

And to add an item in the same end would require us to do all this re-indexing again.

This brings the add and remove operations to O(n) if they are being done at the beginning end of the stack.

So if we use an array list to implement a stack, always do the operations at the end, not at the beginning of the array list.

Usually stacks are displayed like this

| value | index |

|---|---|

| 7 | 3 |

| 23 | 2 |

| 3 | 1 |

| 11 | 0 |

Just like an array list we can add/remove items from either ends as long it's the same end.

Our stack could look like this. null terminated end at the bottom of the stack:

Or null terminated end at the beginning of the stack:

So let's analyse which one is better from the Big O perspective:

| 11 | → | 3 | → | 23 | → | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| head | tail |

11 |

→ | 3 | → | 23 | → | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

head |

tail |

| 11 | → | 3 |

→ | 23 | → | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| head | tail |

| 11 | → | 3 | → | 23 |

→ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| head | tail |

| 11 | → | 3 | → | 23 | → | _NULL_ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| head | tail |

| 11 | → | 3 | → | 23 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| head | tail |

It's O(n) to remove from the end because we would have to iterate over the items until we reach the last item and remove it.

| 11 | → | 3 | → | 23 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| head | tail |

| 11 | → | 3 | → | 23 | → | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| head | tail |

| 11 | → | 3 | → | 23 | → | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| head | tail |

It's O(1), as we can just point from the tail to it, and that would put it back on.

| → | 3 | → | 23 | → | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| head | tail |

| → | 3 | → | 23 | → | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

head |

tail |

| 3 | → | 23 | → | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| head | tail |

It's O(1), as we just pointed the head to the next item.

| 11 | → | 3 | → | 23 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| head | tail |

7 |

→ | 11 | → | 3 | → | 23 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| head | tail |

7 |

→ | 11 | → | 3 | → | 23 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

head |

tail |

| 7 | → | 11 | → | 3 | → | 23 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| head | tail |

It's O(1) as well, as we just pointed to the next element after the head and pointed the head to the new added item.

This means that from the Big O perspective, using a linked list to implement a stack doing operations at the beginning of the linked list is better than at the end of it.

So when we are using a linked list when implementing a stack we always want it to look like this:

With the null terminated end at the bottom.

| 11 |

| ↓ |

| 3 |

| ↓ |

| 23 |

| ↓ |

| 7 |

| ↓ |

| NULL |

Some methods we wrote for the linked list that we can use in our stack:

removeFirst()- calledpop()for stackprepend()- calledpush()for stack

And we had head and tail | || | --- | --- | | 11 |head| | ↓ || | 3 || | ↓ || | 23 || | ↓ || | 7 |tail| | ↓ || | NULL ||

since we are going to represent a stack vertically, we are going to change those names to top and bottom.

| 11 | top |

| ↓ | |

| 3 | |

| ↓ | |

| 23 | |

| ↓ | |

| 7 | bottom |

| ↓ | |

| NULL |

But in a stack we do everything from the top, we don't even need that bottom pointer, then.

| 11 | top |

| ↓ | |

| 3 | |

| ↓ | |

| 23 | |

| ↓ | |

| 7 |

class Node {

int value;

Node next;

Node(int value) {

this.value = value;

}

}

class Stack {

private Node top;

private int height;

public Stack(int value) {

bottom = new Node(value);

height = 1;

}

public void printStack() {

Node temp = top;

while(temp != null) {

System.out.println(temp.value);

temp = temp.next;

}

}

public Node getTop() {

return top;

}

public int getHeight() {

return height;

}

}

or prepend for a LinkedList First we check if the size is zero, if it is we just set the top to the new node. If not then the newNode points to the top, and then we set the new top as the newNode.

public void push(int value) {

Node newNode = new Node(value);

if(height == 0) {

top = newNode;

} else {

newNode.next = top;

top = newNode;

}

height++;

}

But as we can see, we are checking the height to avoid setting the next when we don't have items in the stack. For that we can just simplify the code like this:

public void push(int value) {

Node newNode = new Node(value);

if (height != 0) {

newNode.next = top;

}

top = newNode;

height++;

}

or removeFirst for LinkedList

public Node pop() {

if(height == 0) return null;

Node poppedItem = top;

top = top.next;

poppedItem.next = null;

height--;

return poppedItem;

}

Is just when you get in line, people can get in line behind you, and when you remove someone from the line, it's always the first person in line out of the line.

That's FIFO = First In First Out

add something to queue = enqueued something

remove something from the queue = dequeued something

dequeue or enqueue on the end of the list

| 11 | 3 | 23 |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 |

| 11 | 3 | 23 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 11 | 3 | 23 |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 |

No re-indexing needed. So it's O(1).

But on the other end, if we do the operations at the beginning of the list.

| 11 | 3 | 23 |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 |

| 7 | 11 | 3 | 23 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 |

| 7 | 11 | 3 | 23 |

|---|---|---|---|

0 |

1 | 2 |

| 7 | 11 | 3 | 23 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 |

2 |

| 7 | 11 | 3 | 23 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 |

| 7 | 11 | 3 | 23 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

We can see that we need to do the re-indexing for enqueuing and for dequeueing, this means both operations are O( n).

We could say that for the queue we want to:

- enqueue in the beginning of the list

- dequeue on the end of the list

But we would still have one operation O(1) and another O(n).

And this applies to the other way around as well.

We need to go through the whole list, until the tail.

11 |

→ | 3 | → | 23 | → | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| head | tail |

| 11 | → | 3 |

→ | 23 | → | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| head | tail |

| 11 | → | 3 | → | 23 |

→ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| head | tail |

| 11 | → | 3 | → | 23 | → | _NULL_ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| head | tail |

| 11 | → | 3 | → | 23 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| head | tail |

It's O(n) to remove from the end because we would have to iterate over the items until we reach the last item and remove it.

Add:

| 11 | → | 3 | → | 23 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| head | tail |

| 11 | → | 3 | → | 23 | → | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| head | tail |

| 11 | → | 3 | → | 23 | → | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| head | tail |

It's O(1), as we can just point from the tail to it, and that would put it back on.

Remove:

| → | 3 | → | 23 | → | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| head | tail |

| → | 3 | → | 23 | → | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

head |

tail |

| 3 | → | 23 | → | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| head | tail |

It's O(1), as we just pointed the head to the next item.

Add:

| 11 | → | 3 | → | 23 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| head | tail |

7 |

→ | 11 | → | 3 | → | 23 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| head | tail |

7 |

→ | 11 | → | 3 | → | 23 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

head |

tail |

| 7 | → | 11 | → | 3 | → | 23 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| head | tail |

It's O(1) as well, as we just pointed to the next element after the head and pointed the head to the new added item.

So to summarize:

- From the end (Add: O(1) Remove: O(n))

- From the beginning (Add: O(1) Remove: O(1))

So as we are implementing a queue, we want to do each operation in a different end.

We don't want to remove from the end, as it's O(n), so we will Add on the end of the linked list.

And what's left is Remove from the beginning of the linked list.

This way we make sure all the operations will be O(1).

And instead of head and tail we're going to have first and last.

| 7 | → | 11 | → | 3 | → | 23 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| first | last |

class Node {

int value;

Node next;

Node(int value) {

this.value = value;

}

}

class Queue {

private Node first;

private Node last;

private int length;

public Queue(int value) {

Node newNode = new Node(value);

first = last = newNode;

length = 1;

}

}

public void enqueue(int value) {

var newNode = new Node(value);

if (length == 0) {

first = newNode;

} else {

last.next = newNode;

}

last = newNode;

length++;

}

public Node dequeue() {

if (length == 0) return null;

Node toBeDequeued = first;

if (length == 1) {

first = null;

last = null;

} else {

first = first.next;

toBeDequeued.next = null;

}

length--;

return toBeDequeued;

}

We've already seen a tree, a Linked List is a tree that doesn't fork.

That would be the same as:

{

"value"=4,

"left"= {

"value"=3,

"left"= null,

"right"= null

},

"right"= {

"value"=23,

"left"= null,

"right"= null

},

}

As we wrote in way where we can have one node on each side, it means that we can have just two nodes under a top one , and that's what makes it a binary tree.

But there is no rule that a tree has to be a binary tree. We could have a node pointing to 100 nodes.

It's when every node either points to zero or two nodes.

if we remove the last child nodes. The tree will still be Full, but now it is a Perfect tree.

Perfect means that any level on the tree is completely filed with child nodes.

Examples of perfect trees:

Not a perfect tree, but still Full:

A perfect tree is a complete tree, being filed from left to right with no gaps.

But if we add a node under the 12 node. The tree will no longer be full, nor perfect. But it would still be perfect.

If we add one more node, filling this from left to right, it remains complete, but it is now also full now.

But it is not perfect because we haven't filled it all the way across. But if we do:

These two child nodes because they share the same parent, they are also called siblings.

Every node can only have one parent.

If you see two parents sharing a child node, then is it not a tree.

The child nodes of course can also be parent nodes.

And these nodes at the bottom, they don't have any children, and a node that doesn't have children is called Leaf.

Let's say we have one node with 47 in our tree, and we're going to add another node with a binary search tree.

- If the number is greater than parent, it goes on the right.

- if the number is smaller than parent, it goes on the left.

So if we add a node with the value 76. It would look like this:

And if we add another node, but now with the value 52. It is smaller than 47, but as there is already a node added in the right (the 76), we compare the new node(52) with the 76 node.

And place it on th left, as it's smaller than 76.

It would look like this:

Now if we add two nodes with value 21 and 82:

Adding 18 and 27:

- From any node, all nodes below it to the right are going to be greater than that node.

- From any node, all nodes below it to the left are going to be smaller than that node.

The number of nodes in this tree:

Can be calculated using:

2^1 - 1 = 1

But if we add a second level of nodes:

The total comes to: 2**^2** - 1 = 3

And if added a third level of nodes:

Can be written as: 2**^3** - 1 = 7

And as we get into very large number of nodes, that -1 is insignificant.

So we say that it's approximately 2**^3**, 2**^2** and 2**^1**.

Now if we're going to look for a node in this tree:

it's going to take one step. Obviously.

So we had 2^1 nodes, and it took us one step to find the node.

Now if we're going to look for number **76** in this tree:

it's going to take two steps. So we had 2^2 nodes, and it took us two steps to find a node.

Now if we're going to look for number 27 in this tree:

it's going to take three steps. So we had 2^3 nodes, and it took us three steps to find a node.

To find, add and remove nodes on this tree it will always be three steps.

Meaning that these methods are all O(log n). That is very efficient!

So remember, O(log n) is achieved by doing divide and conquer.

Let's visualize how we do that by using a bigger tree:

Let's break down how are the steps to find the number 49 in the tree:

Starting from the top of the tree we decide if we need to go left or right:

Based on what we know about Binary Search Trees, left is for numbers smaller than the current node, and right for

greater:

Based on what we know about Binary Search Trees, left is for numbers smaller than the current node, and right for

greater:

So we find ourselves in the 76 node, and just by doing that we made it where we never have to look at anything that's on the left of the 47 node.

So we are basically removing half of the tree from the search.

That's not a big deal when you have a small tree, but if we had a million items in the tree, there would be half a million items we would not have to look at.

Continuing on search for the node 49, from where we are we would have to go to the left, because 49 is smaller than 52.

This time we cut out every node on the right of the 76 node. Because numbers bigger than 76 are irrelevant for our search.

By going to the left node (49 is smaller than 52) we have done the cut out again, but this time there was only the ** node 63** on the right.

And we finally find ourselves in the node 49 🎆.

This was: Divide and Conquer!

For calculating time complexity, so far we have used a perfect tree.

For measuring the best possible scenario we use: OMEGA Ω.

But we are more likely to see a tree that looks like this:

Even in this situation we can say that it's roughly O(log n).

But how does a worst case scenario look like?

A worse case would be if we had a node, and then the next node was greater than and goes to the right, and then the next node was greater than and goes to the right as well, and then the next node was greater than and goes to the right as well.

And it just keeps going on and on in a straight line.

As you can see, a tree that never forks it's essentially a singly linked list.

So if we want to look for the 91 node, how many steps would it take for this tree?

- 47 ❌ 1st step

- 76 ❌ 2nd step

- 82 ❌ 3rd step

- 91 ✅ 4th step

It would be four steps, and we have four nodes in the tree.

That is O(n).

So the Big O of a Binary Search Tree technically is O(n), not O(log n).

But what we assume with a Binary Search Tree is that it's not going to be a straight line.

And we treat it as O(log n). Not as a O(n) Data structure.

Technically the Big O for the Binary Search Tree is a O(n), but we treat it as O(log n).

All the three methods of a Binary Search Tree are:

- lookup()

- remove()

- insert()

For finding an item in a linked list, we would have to iterate through the entire list until we found the number 91.

That makes it O(n). While the BST is O(log n).

For removing an item in a linked list, we would have to iterate through the entire list until we found the number 91 and remove it.

That makes it O(n). While the BST is O(log n).

For inserting, there is no advantage to keeping it sorted, because we would have to go through the list either way to find an item.

We just add the item to the end, and that is actually faster with a linked list.

Inserting into a linked list it's a single step process, so O(1).

Making the insert() method faster with a Linked List than with a Binary Search Tree.

Who is the faster and what:

| Data Structure | Linked List and Array List | Binary Search Tree |

|---|---|---|

| lookup() | O(n) | ✅ O(n) treated as O(log n) |

| remove() | O(n) | ✅ O(n) treated as O(log n) |

| insert() | ✅ O(1) | O(n) treated as O(log n) |

Our not would look like this:

{

"value"=4,

"left"= null,

"right"= null,

}Those would be our properties for our Node class.

public class Node {

int value;

Node left;

Node right;

Node(int value) {

this.value = value;

}

}For the BinarySearchTree class, we need to clarify something first:

Each node has to have a pointer pointing to it, or it's going to get garbage collected.

Every node here has something pointing to it except that top node.

That's why on the linked list we have head pointing to the first node. So the nodes won't get garbage collected.

As we need to do something similar with the tree, we are going to call the pointer to the first node root.

So the code will look like this:

public class BinarySearchTree {

private Node root;

public BinarySearchTree(int value) {

this.root = new Node(value);

}

}When implementing a linked list we had a field to control how many items we had in the list.

But the Binary Search Tree we won't do that.

We can initialize a tree that doesn't have any nodes. And then we add the first node with the insert() method.

public class BinarySearchTree {

private Node root;

public BinarySearchTree() {

root = null;

}

}Because we are not setting the root to any default value, the default value it's null.

So the class don't need a constructor.

public class BinarySearchTree {

private Node root;

public Node getRoot() {

return root;

}

}Let's go through the steps before implementing the method:

Let's say we are adding the number 27 to the Binary Search Tree.

- create newNode with value 27.

- if current == null: insert

- else:

- move to next:

- if newNode < current: go left

- else: go right

- move to next:

- if current == null: insert

- else:

- move to next:

- if newNode < current: go left

- else: go right

- move to next:

As you can see, we are repeating the steps, and that means that a while loop is needed here.

So we can re-write the steps as:

- create newNode with value 27.

- create temp = root

- while loop

- if temp == null: insert

- if newNode < temp: go left

- if temp == null: insert newNode

- else: move to next node

- else: go right

But if the tree is empty we don't want to create unnecessary temp variables. So we add a line after the creation of newNode:

- create newNode with value 27.

- if root == null then root = newNode and return true.

- create temp = root

- while loop

- if temp == null: insert

- if newNode < temp: go left

- if temp == null: insert newNode

- else: move to next node

- else: go right

Another edge case would be handling duplication. Let's say we want to add the number 76 in our tree.

We can't insert a value that we already have in the Binary Search Tree.

So let's add a verification for every iteration:

- create newNode

- if root == null then root = newNode and return true.

- create temp = root

- while loop

- if newNode == temp return false

- if temp == null: insert

- if newNode < temp: go left

- if temp == null: insert newNode

- else: move to next node

- else: go right

public boolean insert(int value) {

// create newNode

Node newNode = new Node(value);

// if root == null then root = newNode and return true

if(root == null) {

root = newNode;

return true;

}

//create temp = root

Node temp = root;

while(true) {

// if newNode == temp return false

if(newNode.value == temp.value) return false;

// if newNode < temp: go left

if(newNode.value < temp.value) {

// if temp == null: insert newNode

if(temp.left == null) {

temp.left = newNode;

return true;

}

// else: move to next node

temp = temp.left;

// else: **go right**

} else {

// if temp == null: insert newNode

if(temp.right == null) {

temp.right = newNode;

return true;

}

// else: move to next node

temp = temp.right;

}

}

}It will return true or false based on the presence of the provided item in the tree.

Let's break it down in steps first:

- if root == null return false (maybe we won't need this step)

- create temp = root

- while (temp != null) loop

- if searchedValue == temp return true

- if searchedValue < temp: go left

- temp = temp.left

- else if searchedValue > temp: go right

- temp = temp.right

- while loop is done: return false

public boolean contains(int searchedValue) {

// create temp = root

Node temp = root;

while (temp != null) {

// if searchedValue == temp return true

if (searchedValue == temp.value) return true;

// if searchedValue < temp: go left

if (searchedValue < temp.value) {

temp = temp.left;

// if searchedValue > temp: go right

} else {

temp = temp.right;

}

}

// while loop is done: return false

return false;

}If you notice, we didn't include the code for the step:

- if root == null return false

With the code we wrote above:

- when the root node is null

- it would be assigned to temp

- and would not go inside the loop because the condition is temp != null

- and then it would return false.

Let's say we have this address space in memory:

| address space | |

|---|---|

| 0 | |

| 1 | |

| 2 | |

| 3 | |

| 4 | |

| 5 | |

| 6 | |

| 7 |

We can create this by using an array, and then in this array we are going to store key-value pairs.

Let's imagine an inventory for a hardware store.

Example of key-value pair:

{ "nails"= 1000 }

Later we will write the code for a hashmap.

We are going to run the hash on the key, from the key-value pair.

So every letter has an ASCII text numerical value, and what we're going to do is run a calculation on all the numbers associated with these letters.

The hash would run on the key and gives us an address. That is going to be one of the indexes in the array, and that's where we store our key value.

- It's a ONE WAY process!

- you can get 2 when passing

"nails"to the hash. - but you CAN NOT get

"nails"when passing 2 to the hash.

- you can get 2 when passing

- It's deterministic:

- When we run

"nails"through this, we will always get the same address.

- When we run

So let's add more items to our address space, the method signature would look like this:

set(key, value)

So, for set("nails", 1000) we got 2:

| address space | |

|---|---|

| 0 | |

| 1 | |

| { "nails"= 1000 } | 2 |

| 3 | |

| 4 | |

| 5 | |

| 6 | |

| 7 |

For set("screws", 800) we got 6:

| address space | |

|---|---|

| 0 | |

| 1 | |

| { "nails"= 1000 } | 2 |

| 3 | |

| 4 | |

| 5 | |

| { "screws"= 800 } | 6 |

| 7 |

For set("nuts", 1200) we got 2:

We already have an item on the index 2, what do we do on this situation?

This situation is called a collision, because we already have something at the index 2.

What we don't want to do is just overwrite this. We want to be able to keep both items in the index 2.

| address space | |

|---|---|

| 0 | |

| 1 | |

| { "nails"= 1000 } { "nuts"= 1200 } |

2 |

| 3 | |

| 4 | |

| 5 | |

| { "screws"= 800 } | 6 |

| 7 |

There are multiple ways of storing multiple items in a particular address. We are going to talk about this later.

For set("bolts", 1400) we got 4:

| address space | |

|---|---|

| 0 | |

| 1 | |

| { "nails"= 1000 } { "nuts"= 1200 } |

2 |

| 3 | |

| { "bolts"= 1400 } | 4 |

| 5 | |

| { "screws"= 800 } | 6 |

| 7 |

Now that we have our Hash Table filled with some items, let's see how would it work to retrieve an item.

if we call get("bolts"):

Step 1. We can run "bolts" through the same hash map we do when adding an item (set("bolts", 1400)).

Step 2. And then the hash method will give us the index of 4 for the input "bolt".

- Remember that the hash method is deterministic so everytime for the same input ("bolts" for e.g.), it will give us the same result (index of 4).

Step 3. Then with the index we can just write the get method to return the value that's associated with that key-value pair (1400 on this case).

The Step 3 would be a bit more complex if we want to get("nails"), because after calculating the index 2,

we would have to iterate through all the keys on that index, and then return the value associated with the key "nails".

We already talked about one of the ways to deal with collisions.

Where we just put the next key-value pair at the same address, even if there's already one there. This method is called Separate Chaining.

set("nuts", 1200):

| address space | |

|---|---|

| 0 | |

| 1 | |

| { "nails"= 1000 } { "nuts"= 1200 } |

2 |

| 3 | |

| { "bolts"= 1400 } | 4 |

| 5 | |

| { "screws"= 800 } | 6 |

| 7 |

Another way of doing this is: if there is an item already at the address where we want to put something, you just go to the next open spot and put it there.

set("nuts", 1200):

| address space | |

|---|---|

| 0 | |

| 1 | |

| { "nails"= 1000 } | 2 |

| { "nuts"= 1200 } | 3 |

| { "bolts"= 1400 } | 4 |

| 5 | |

| { "screws"= 800 } | 6 |

| 7 |

set("paint", 50):

| address space | |

|---|---|

| 0 | |

| 1 | |

| { "nails"= 1000 } | 2 |

| { "nuts"= 1200 } | 3 |

| { "bolts"= 1400 } | 4 |

| { "paint"= 50 } | 5 |

| { "screws"= 800 } | 6 |

| 7 |

This is called Linear Probing.

And this is one of the types of open addressing.

So Separate Chaining and Linear Probing are the most common way of dealing with collisions.

We are going to look more at Separate Chaining where we have many key-value pairs at one address.

| address space | |

|---|---|

| 0 | |

| 1 | |

| { "nails"= 1000 } { "nuts"= 1200 } { "paint"= 50 } |

2 |

| 3 | |

| { "bolts"= 1400 } | 4 |

| 5 | |

| { "screws"= 800 } | 6 |

| 7 |

The way we will achieve it is by having a LinkedList on each one of these addresses.

Linked Lists is a common way of implementing Separate Chaining and putting multiple items at a particular address.

And that's how we are going to deal with Collision.

Let's make a change to our address space.

| address space | |

|---|---|

| 0 | |

| 1 | |

| 2 | |

| 3 | |

| 4 | |

| 5 | |

| 6 | |

| 7 |

By removing the last index on the bottom:

| address space | |

|---|---|

| 0 | |

| 1 | |

| 2 | |

| 3 | |

| 4 | |

| 5 | |

| 6 |

We see that our address space has now seven indexes (from 0 to 6).

And the reason why we want to do it is that we will have fewer collisions if our address space has a prime number of addresses.

public class HashTable {

private int size = 7;

private Node[] dataMap;

public HashTable() {

dataMap = new Node[size];

}

public void printTable() {

for (int i = 0; i < 7; i++) {

System.out.println(i + ":");

Node temp = dataMap[i];

while (temp != null) {

System.out.println("{ " + temp.key + ":" + temp.value + " }");

temp = temp.next;

}

}

}

// Node example: { "nails"= 1000 }

class Node {

private String key;

private int value;

private Node next;

public Node(String key, int value) {

this.key = key;

this.value = value;

}

}

}Main Class

public class Main {

public static void main(String[] args) {

HashTable myHt = new HashTable();

myHt.printTable();

}

}

/* EXPECTED OUTPUT

0:

1:

2:

3:

4:

5:

6:

*/Some steps that the hash method should have:

- Get a key as the parameter

- Start the hash with the value 0

- Convert the key to a char array

- Loop through the array of chars

-

Assign hash to:

hash plus ASCII value of the char multiplied by a prime number

-

We multiply it by a prime number because this increases the randomness of the result

-

We chose the prime number 23, so till now, the code would look like:

hash = (hash + asciiValue * 23) -

Then we use modulo of the dataMap length (that in our case is 7).

hash = (hash + asciiValue * 23) % dataMap.length -

Anything that we divide by 7, would have a remainder value from 0 to 6 at maximum, that is exactly our address space.

-

So this equation is always going to return a number that is one of the indexes in this array.

-

-

- After going through all the characters, we will return hash.

- That is always going to be a number that is 0 through 6.

The code for our _hash()_ method would look like this:

public int hash(String key) {

int hash = 0;

char[] keyChars = key.toCharArray();

for (int i = 0; i < keyChars.length; i++) {

int asciiValue = keyChars[i];

hash = (hash + asciiValue * 23) % dataMap.length;

}

return hash;

}Some steps that the set method should have:

- Calculate the index using hash(key)

- Create a newNode using key and value parameters

- check dataMap on the calculated index:

- If is null, then we just assign the newNode

- If is not null, then we go through all the nodes.next.next.next... until we find the last one. And then we point the last node to the newNode.

public void set(String key, int value) {

int addressIndex = hash(key);

Node newNode = new Node(key, value);

if(dataMap[addressIndex] == null) {

dataMap[addressIndex] = newNode;

} else {

Node temp = dataMap[addressIndex];

while(temp.next != null){

temp = temp.next;

}

temp.next = newNode;

}

}Main Class

public class Main {

public static void main(String[] args) {

HashTable myHt = new HashTable();

myHt.set("nails", 100);

myHt.set("tile", 50);

myHt.set("lumber", 80);

myHt.set("bolts", 200);

myHt.set("screws", 140);

myHt.printTable();

}

}

/* EXPECTED OUTPUT

1:

2:

3:

{ screws:140 }

4:

{ bolts:200 }

5:

6:

{ nails:100 }

{ tile:50 }

{ lumber:80 }

*/Some steps that the get method should have:

- Calculate the index using hash(key)

- check dataMap on the calculated index:

- If is null, then return null

- If is not null, then we go through all the nodes looking for the one that matches they given key. And then we return the value of that key-value pair.

public int get(String key) {

int addressIndex = hash(key);

Node temp = dataMap[addressIndex];

while(temp != null){

if(key.equals(temp.key)) {

return temp.value;

}

temp = temp.next;

}

return 0;

}Main Class

public class Main {

public static void main(String[] args) {

HashTable myHt = new HashTable();

myHt.set("nails", 100);

myHt.set("tile", 50);

myHt.set("lumber", 80);

myHt.printTable();

System.out.println("Value of lumber: " + myHt.get("lumber"));

System.out.println("Value of bolts: " + myHt.get("bolts"));

}

}

/* EXPECTED OUTPUT

0:

1:

2:

3:

4:

5:

6:

{ nails:100 }

{ tile:50 }

{ lumber:80 }

Value of lumber: 80

Value of bolts: 0

*/For this method we're going to get all the keys our of the Hash Table, put them in array list and return that array list.

public ArrayList keys() {

ArrayList<String> allKeys = new ArrayList<>();

for (int i = 0; i < dataMap.length; i++) {

Node temp = dataMap[i];

while(temp != null) {

allKeys.add(temp.key);

temp = temp.next;

}

}

return allKeys;

}Main Class

public class Main {

public static void main(String[] args) {

HashTable myHt = new HashTable();

myHt.set("nails", 100);

myHt.set("tile", 50);

myHt.set("lumber", 80);

myHt.set("bolts", 200);

myHt.set("screws", 140);

myHt.printTable();

System.out.println("Keys:");

System.out.println(myHt.keys());

}

}

/* EXPECTED OUTPUT

0:

1:

2:

3:

{ screws:140 }

4:

{ bolts:200 }

5:

6:

{ nails:100 }

{ tile:50 }

{ lumber:80 }

Keys:

[screws, bolts, nails, tile, lumber]

*/Because the hash method has to be run every time we add an item or we get an item, we have to calculate what's the Big O of the hash() method.

The hash() method is O(1) because it will execute the same number of operations regardless of the number of items that are already in the hash table.

Now let's walk through setting an item:

- We would run it through our hash method, and it would give us the address 0.

- Using this index we would assign the key-value pair to the calculated address.

That is a single step, so the set method is O(1).

- We would run it through our hash method, and it would give us the address 6.

- Using this index we would directly access the address 6 and return the value of the pair in there.

That is a single step, so could we say that the get method is O(1)?

Hmmmmmm. Before answering this question, how would the get("screws", 1000) looks like if our hash table looked like this:

- We would run it through our hash method, and it would give us the address 2.

- Using this index we would directly access the address 2.

- And then we have to iterate through the entire list of pairs to find the one with the matching key and return the value from the pair.

You would think that this would be O(n), but when working with the hash table we assume that the hash method is going to create very random addresses, and your hash table is going to look something more like this:

A very good hash method means:

- Having a larger address space.

- Randomizing where the items are put.

And because of that we treat getting an item and setting an item in a hash table as O(1).

How can we write a code to check if the following two arrays have an item in common?

| 1 | 3 | 5 |

|---|---|---|

| 3 | 4 | 5 |

The most simple solution is using nested for loops. But that would be the inefficient way. Let's see why:

public class Main {

public static void main(String[] args) {

int[] array1 = {1, 3, 5};

int[] array2 = {2, 4, 5};

System.out.println(itemInCommon(array1, array2));

}

public static boolean itemInCommon(int[] array1, int[] array2) {

for (int i : array1) {

for (int j : array2) {

if (i == j) return true;

}

}

return false;

}

}if we check the itemInCommon() method we see that we had to do nested loops for checking the existence of first array items in the second one. So the Big O for this solution is O(n²).

Now let's see how we can do this much more efficiently, with a Hash Table.

public static boolean itemInCommon(int[] array1, int[] array2) {

Hashtable<Integer, Boolean> hs = new Hashtable();

for (int i : array1) {

hs.put(i, true);

}

for (int j : array2) {

if(hs.get(j) != null) return true;

}

return false;

}We can see that now we are:

- first populating a Hash Table with all the items in the first array

- in the second for loop we just call the get for each of its elements

- if the get() returns is not null it means the element is contained in the Hash Table, so we return true.

So we have two not nested for loops. This makes it O(2n), and by dropping the constant we end up with O(n).

To look at graphs we first we need to understand two concepts:

-

a Vertex or a Node.

plural: vertices

-

an Edge or Connection

In the image above we can see that the vertex 3 can have an edge with many vertices. Meaning that there is no limit to how many other vertices a vertex can connect to.

Let's say do you want to go from 76 to 82.

You would say that you don't want to go from 76 to 44 to 82 because that would be two hops.

You will probably say that the best way to do it is from 76 to 82, because that would need a single hop.

Most of the time want to go the most direct route.

Why not every single time? Some graphs can have weighted edges.

The best path would be the one with less accumulated weight.

Imagine this same graph but with weights:

Now the direct path would cost us 15. And the longer path would accumulate only 5.

To bring this into the real world, let's think about starting point and destination in a Google Maps.

I want to go to the Barber. What would be the quickest way I can get there?

If I go the direct path to the Barber, it would cost me 25 minutes. Because probably that street is having some bad traffic.

But in the other hand, If I do the path where I pass by the mall. It would take me a total of 5 minutes to the to my Barber.

So in this case, the longest path was the fastest one.

Another important concept of graphs is that when we see an edge without any arrows, it means it's a bidirectional edge.

A bidirectional example would be in facebook connections.

Your friend is friends with you and you are friends with your friend.

So it's a bidirectional edge. It goes both ways.

Now on twitter or instagram, when you follow a celebrity:

You are following the celebrity, but they don't follow you back. That is directional.

Trees are a form of graph, but they have the limitation that each node can only point to two other nodes directionally.

Linked Lists are a form of a Tree.

So if:

Linked List = Tree

Tree = Graph

Therefore:

Linked List = Graph

Linked List is a form o a Graph with the limitation that each node can only point to one, directionally.

Let's represent this graph in an Adjacency Matrix.

let's start from the A vertex. It has two edges with B and E, so we are going to fill those with 1s.

| A | B | C | D | E | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 1 |

1 |

|||

| B | |||||

| C | |||||

| D | |||||

| E |

And of course in an adjacency matrix A can not have a vertex with itself, so we put a 0 there.

| A | B | C | D | E | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 0 |

1 | 1 | ||

| B | |||||

| C | |||||

| D | |||||

| E |

A does not have an edge with C and D, so we fill it with 0s.

| A | B | C | D | E | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 0 | 1 | 0 |

0 |

1 |

| B | |||||

| C | |||||

| D | |||||

| E |

That's it for vertex A.

Now let's do the same for vertex B:

| A | B | C | D | E | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| B | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| C | |||||

| D | |||||

| E |

And so on until we complete our matrix.

| A | B | C | D | E | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| B | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| C | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| D | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| E | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

So this axis represents the actual vertex.

| A | B | C | D | E | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

A |

0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

B |

1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

C |

0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

D |

0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

E |

1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

And this axis is the items it has an edge with.

A |

B |

C |

D |

E |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| B | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| C | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| D | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| E | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

An interesting thing about adjacency matrix, that we said that:

- A can't point to A

- B can't point to B ...

We are always going to have this 45 degree line of zeros.

| A | B | C | D | E | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 0 |

1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| B | 1 | 0 |

1 | 0 | 0 |

| C | 0 | 1 | 0 |

1 | 0 |

| D | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

1 |

| E | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

And if we have a bidirectional matrix like we have in the example, we will always have a mirror image on each of the sides of the line. That looks like that:

| A | B | C | D | E | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 0 | 1 |

0 | 0 | 1 |

| B | 1 |

0 | 1 |

0 | 0 |

| C | 0 | 1 |

0 | 1 |

0 |

| D | 0 | 0 | 1 |

0 | 1 |

| E | 1 |

0 | 0 | 1 |

0 |

But this is only if these are bidirectional.

To exemplify that, let's change the direction of an edge and build the matrix for it: Now A points to B but B is not pointing back.

The matrix would look like:

| A | B | C | D | E | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| B | 0 |

0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| C | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| D | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| E | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

As you can see, on the cell B -> A we have a zero now. So we have lost our symmetry across that 45 degree line.

Now let's say that our edges have weights:

So if edges are weighted in an adjacency matrix, we will just store these weights in the matrix:

| A | B | C | D | E | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 0 | 2 |

0 | 0 | 10 |

| B | 2 |

0 | 4 |

0 | 0 |

| C | 0 | 4 |

0 | 6 |

0 |

| D | 0 | 0 | 6 |

0 | 8 |

| E | 10 |

0 | 0 | 8 |

0 |

Adjacency List is just another way of representing a graph.

And we'll do this by using a HashMap.

- Key: the vertex

- Value: a list with all the edges.

Would look something like this:

{

"A" = ["B", "E"]

}Ps: Notice that we are using letters but the content of the node could be any String, not only a single character.

So the entire graph would look like this:

{

"A" = ["B", "E"],

"B" = ["A", "C"],

"C" = ["B", "D"],

"D" = ["C", "E"],

"E" = ["A", "D"]

}As we have seen before, there are two ways of representing a graph, as an Adjacency Matrix and as an Adjacency List.

We are going to look at the Big O of both.

In an Adjacency List we are going to store that vertex and each one of the edges.

{

"A" = ["B", "E"],

"B" = ["A", "C"],

"C" = ["B", "D"],

"D" = ["C", "E"],

"E" = ["A", "D"]

}In an Adjacency Matrix we store those edges, but we also have to store everything that it is not connected to, all of these zeros:

| A | B | C | D | E | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 0 |

1 | 0 |

0 |

1 |

| B | 1 | 0 |

1 | 0 |

0 |

| C | 0 |

1 | 0 |

1 | 0 |

| D | 0 |

0 |

1 | 0 |

1 |

| E | 1 | 0 |

0 |

1 | 0 |

And that is a big advantage of the adjacency list.

Space complexity for

-

Adjacency Matrix:

- Number of vertices squared: O( |V|² )

-

Adjacency List:

- Number of vertices plus number of edges: O( |V| + |E| )

From a Space Complexity perspective, the adjacency list is better.

Imagine we want to add a new vertex F to our graph. Not connected to anything.

In order to add a new vertex it's just a matter of adding it into the list:

{

"A" = ["B", "E"],

"B" = ["A", "C"],

"C" = ["B", "D"],

"D" = ["C", "E"],

"E" = ["A", "D"],

"F" = []

}Now with the matrix we have to add a bidimensional array to the matrix:

| A | B | C | D | E | F |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| B | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| C | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| D | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| E | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

F |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

As soon as we make the arrays bigger, you have to create new arrays that are bigger. And recreating those arrays if very inefficient.

From a Big O perspective:

- Adjacency Matrix: O( |V|² )

- Adjacency List: O( 1 )

So the adjacency list is much more efficient at adding items.

Let's now see how complex it is to add an edge between B and F vertex.

In order to add a new edge, we need to add the "F" vertex into the "B" edge list, and vice-versa.

{

"A" = ["B", "E"],

"B" = ["A", "C", "F"],

"C" = ["B", "D"],

"D" = ["C", "E"],

"E" = ["A", "D"],

"F" = ["B"]

}For the matrix we just need to change the values from zero to one on the B → F and F → B cells

| A | B | C | D | E | F | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| B | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| C | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| D | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| E | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| F | 0 | 1 |

0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

From a Big O perspective, both adjacency matrix and adjacency list are O( 1 ) to add an edge.

How complex it would be to remove the edge between B and F vertex that we've just added?

In order to remove the edge between B and F, we need to:

- Find B in the hash map

- Then iterate through the edge list and remove F from it

- And then Find F in the hash map

- Then iterate through the edge list and remove B from it

{

"A" = ["B", "E"],

"B" = ["A", "C"],

"C" = ["B", "D"],

"D" = ["C", "E"],

"E" = ["A", "D"],

"F" = []

}In a matrix we just need to change the values from one to zero on the B → F and F → B cells.

| A | B | C | D | E | F | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| B | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| C | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| D | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |